Posters of the Great Patriotic War: weapons of the winners

I.Toidze, 1941

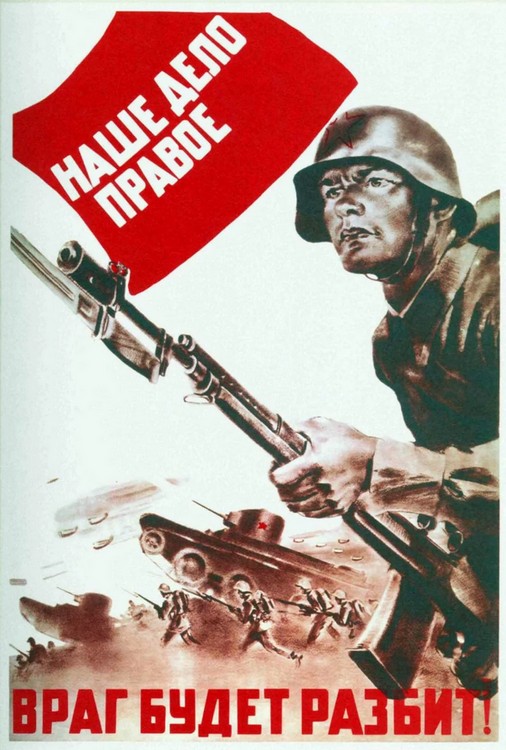

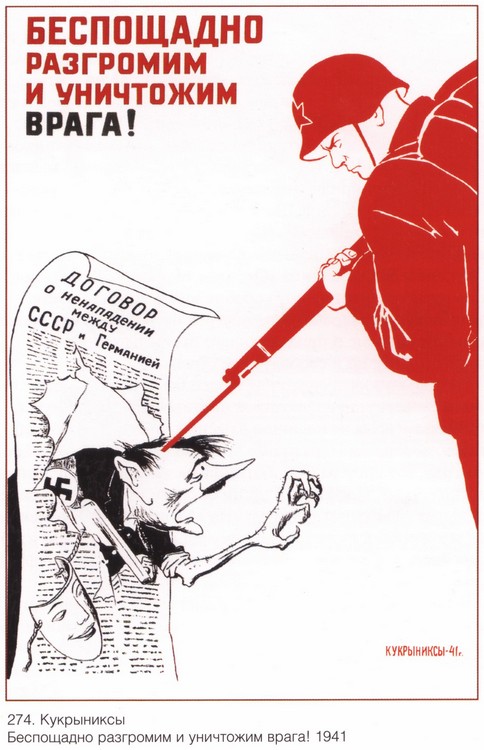

From the first days of the Great Patriotic War, poster artists joined in the fight against the enemy. Among the military posters pasted on the walls of houses on June 23, 1941, was the work of Kukryniksy (Mikhail Kupriyanov, Porfiry Krylov, Nikolai Sokolov) named "We’ll ruthlessly defeat and destroy the enemy!", depicting Hitler treacherously violating the Non-aggression Pact between the USSR and Germany.

In the fight against the enemy, caricature became the main propaganda weapon. Victor Koretsky’s work "Our forces are innumerable" was among the striking works of the first days of the war. This poster, made by the method of photomontage, appealed to the creation of a people's militia to fight the enemy. The artist turned to the symbol of Russian patriotism: Martos’s sculpture of "Minin and Pozharsky", which personified Moscow and the whole country on the poster. The slogan of V. Koretsky’s poster became prophetic: millions of people stood up for the defense of the Motherland in order to defend their freedom and independence.

Shortly after, V. Koretsky created the composition “Be a Hero!” This poster, enlarged several times, was installed along many streets of Moscow.

Irakli Toidze’s poster "The Motherland Calls" became a landmark work, demonstrating a sense of personal responsibility for the fate of his people and country. The portrait individuality of the heroine, combined with the red color of her clothes, symbolizing the Soviet flag, gave I. Toidze's work extraordinary significance and acuteness.

Nikolai Dolgorukov opened his chronicle of the war with a satirical sheet “It has been so ... It will be so!” reminding of the inglorious defeat of Napoleon and compared his end to the future of German fascism.

Among the war sheets made by the Kukryniksy artists, the poster with the text of Samuel Marshak was especially catchy: "We fight bravely; we stab desperately, we are Suvorov’s grandchildren, Chapayev’s children.” The theme of succession of generations for the first time embodied in this poster: Soviet soldiers and national heroes, the outstanding Russian army leaders.

Artist Dmitry Moor used the composition of his famous Civil War poster, “Have you signed up as a volunteer?” under the new slogan: "What have you done to help the front?" The relevance and effectiveness of the poster was so high that it was reprinted in other cities of the country with the translation of the slogan into the national languages of the peoples of the USSR.

The commonwealth of artists, writers and poets made it possible to find an operational form for performing short-run graphic works. From the first days of the war, masters of graphic art began to create daily editions, so-called “TASS Windows” by analogy with the “ROST Windows” of the first post-revolutionary years, in which artists Mikhail Cheremnykh, Victor Denis, Boris Efimov, Pavel Sokolov-Skalya, Viktor Ivanov and others actively participated.

From the first days of the war, “TASS Windows” were organized in Leningrad, which presented the first poster on June 24, 1941. To place the Leningrad “TASS Windows” they found a place in the very center of the city: it was the windows of the former Yeliseyevsky store on Avenue of October 25 (as then Nevsky Avenue was named), then laid with sandbags and covered with boards. This wall of boards became the place where the takes “From the Soviet Information Bureau” and “At the Last Hour” were placed, with large poster of “TASS Windows” to the right and to the left of the bulletins.

In the spring of 1942, Vasily Selivanov, the artist and correspondent of the On Guard of the Motherland newspaper, headed the work at TASS Windows. Artists Vladimir Serov, Vladimir Galba, Boris Leo, Pyotr Magnushevsky and Sergey Pankratov joined him.

V. Serov, 1941

Artist V. Serov,1941

Initially, the posters of the Leningrad “TASS Windows” were made manually, using stencils, and their circulation was quite limited. However, by 1943 the printing base of TASS Windows got strengthened, and the circulation of posters increased, varying from three to six thousand copies. Together with the artists, poets Olga Berggolz, Vissarion Sayanov, Boris Timofeyev, Alexander Flit, Alexander Prokofiev actively participated in the work on the editions of the “Windows”.

During the war years, satirical leaflets under the Action Pencil name and the emblem combining a palette and a rifle with a pencil instead of a bayonet were broadely used in Leningrad.

A day after the outbreak of the war, the first drawing of the "pencil" was created; it was called "Fascism is the enemy of mankind." The authors of the poster were V. Galba, I. Yetz, V. Kurdov, N. Muratov and G. Petrov. Posters of the Action Pencil were delivered to the front, to the ships of the Baltic Fleet, to factories, plants and schools. Using color lithographic printing, the artists created 103 works, which spread around in two million copies.

The posters that I, one of the authors of these lines, saw on the walls of houses in the early days of the war, immediately began to attract my attention with bright colors, catchy patterns, and the character of the performance.

“I wish I could place such a poster at home,” I thought. My father guessed my thoughts and by the end of June 41, he brought me a poster, saying that such posters were placed at his work, and he managed to scribble one of them for me. “I’m sure,” my father continued, “such posters will be produced constantly, and maybe you should pay attention to them and redraw them in your album”.

The poster of artist Alexei Kokorekin, which my father brought me, depicted a crab-shaped, with large claws monster crushed by the powerful butt of a red rifle. On the white field of the poster sheet was a large inscription: “Kill the fascist reptile!” I gladly placed it over the desk where I was doing my homework.

There was an idea to purchase other posters, but it was impossible to do this: posters were not sold in stores, and it was unfeasible to remove them from the walls of houses.

In September 1942, I, Vsevolod Inchik, went to the fifth grade of school number 239 of the Oktyabrsky district, which was known as the "school with lions." Once, my classmates and I were sent to a school next door, which was destroyed and did not work to pick up textbooks, books for reading, and other useful things. When I entered there, I saw two posters in the lobby, and two others in the hallway leading to the library. I was in a condition that occurs in a hunter who saw his prey. But, in order not to show a keen interest in posters, I asked the head teacher accompanying us: “Shall I pick up the posters?” She replied that yes, it was necessary; they would be useful to us.

I did not leave posters at school: I considered them my trophies, which I took out from under the shelling. At home, I unfolded them, four posters of the first days of the war, made by artists D. Shmarinov, V. Serov, V. Odintsov, I. Toidze. They were magnificent and laid foundation of my new collection.

Since then, the collector's passion got ignited in me, and I did not miss the opportunity to replenish my collection. My room and the corridor of our large apartment began to fill with new posters. Some of them I began to copy in my album.

Now I can confess that I was taking posters wherever I had such an opportunity, be that at my school or from the walls of houses, especially when the posters lagged behind the walls under the influence of wind and rain. I understood that I could be punished for this, but I reassured myself that the fate of any poster, wherever it was placed, would turn into a damp, dirty, torn, unnecessary piece of paper.

And here is another case when once more I got a chance to replenish my poster collection. At the end of February 1944, during the light snow break, I was returning from school and walked along Herzen Street (now Bolshaya Morskaya) and saw a small poster on the wall facing the building of the Leningrad Regional Union of Artists. It was the work of my beloved cartoonist Vladimir Galba, whose drawings I often saw in the Leningradskaya Pravda newspaper.

I would not dare to remove the poster from the wall, although that was of no difficulty, because it got wet and was almost falling off the wall. However, having done my homework at home, I remembered the poster. After all, I had no works of Vladimir Galba in my collection, and I had never seen them on the walls of houses!

The evening was coming, it was dark. At such a time, I had never left home alone, and the weather was bad, it snowed wet and strong. If Mom were at home, she would never let me out. But I ventured out and headed for the place where the poster hung. Unfortunately, it was no longer on the wall. It became clear that the wind had ripped it off. Wet snow continued to fall. I realized: most likely, it was lying somewhere on the street, covered with snow. I was in no hurry to return home and began to pace along the wall, raking the snow with my feet. And my efforts were not in vain! Under the snow, I saw the tip of wet paper. I slightly pulled for it, and, oh joy, that was what I was looking for! Back at home, I dried the poster, pasted it, and smoothed it with an iron. Then it began to look it own self. The poster was named "Species of Fritz the Mushrooms." It depicted fascists in the form of various mushrooms. Among them was an orange aspen bolete – Hitler with an aspen stake hammered in his back. Fascist mushrooms were depicted with disgusting physiognomies, which could easily distinguish schizophrenics, maniacs, sadists.

Classmates also gave me posters. Once, my mother brought me a poster she worked as a nurse in the evacuation hospital and, cleaning the room, found a poster in the nightstand, which the fighters were going to use as wrapping paper. Handing it to me, she said: "For you, this poster will not only be interesting, but also relevant, because you have problems with the English language." On the poster, the artist M. Nesterova painted a pretty girl with pigtails sitting at her desk with her hand raised. The text read: “Study well!”

After Leningrad was liberated from the enemy siege, intensive restoration work began in the city. Many students, including our class, were sent to help workers. The work was quite simple. Near house number 4 on Gogol Street (now Malaya Morskaya), students collected bricks that formed a large blockage. We stacked bricks on a wooden stretcher and carried it to a truck that transported debris of construction materials. And on the fence that enclosed the ruined house, there was a poster. It depicted a blond pretty girl in a red beret and gray overalls. In her hands she had the same wooden stretchers as ours, but instead of construction debris, the stretches were loaded with new bricks. The girl portrayed by artist I. Serebryany looked at us as if inviting to help her. The caption on the poster read: “Well, take it!” This one of the best posters of Leningrad artists, not without the help of school friends, was also in my collection.

I kept collecting wartime war posters after the war, but I never held them, as they say, under wraps, but constantly presented them at exhibitions - at schools, in bookstores and libraries.

By the fortieth anniversary of the Great Victory, I organized a large exhibition of my posters, postcards and books at St. Petersburg State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering (which was then called LISI), where I keep working now.

The posters of the Great Patriotic War, stored in museums and in my collection, are the rarest artifacts: weapons of the winners.

Text: Vsevolod Inchik, professor

Tatyana Inchik, full member of the Petrovsky Academy of Sciences and Arts, took part in the preparation of the article